Workplace Gender-Based Violence

Workplace GBV Learning Objectives

Once you complete the learning and exploration activities throughout this section, you will find that you can:

- Define Domestic or Family Violence

- Explain why workplace policies need to have a domestic violence policy as well as anti-harassment and sexual violence policies

- Recognize the warning signs that an employee may be at risk to experience domestic or workplace violence

- Provide different options to offer a victim/survivor support in safer ways

- Identify and explain the most dangerous time for a survivor of domestic violence happens when ____

- Understand that online workplace harassment is increasing

- Feel comfortable establishing protocols to mitigate online harassment and create online safety for employees

- Define survivor centric practices

- Apply the 6 pillars for survivor centric systems and practices/responses

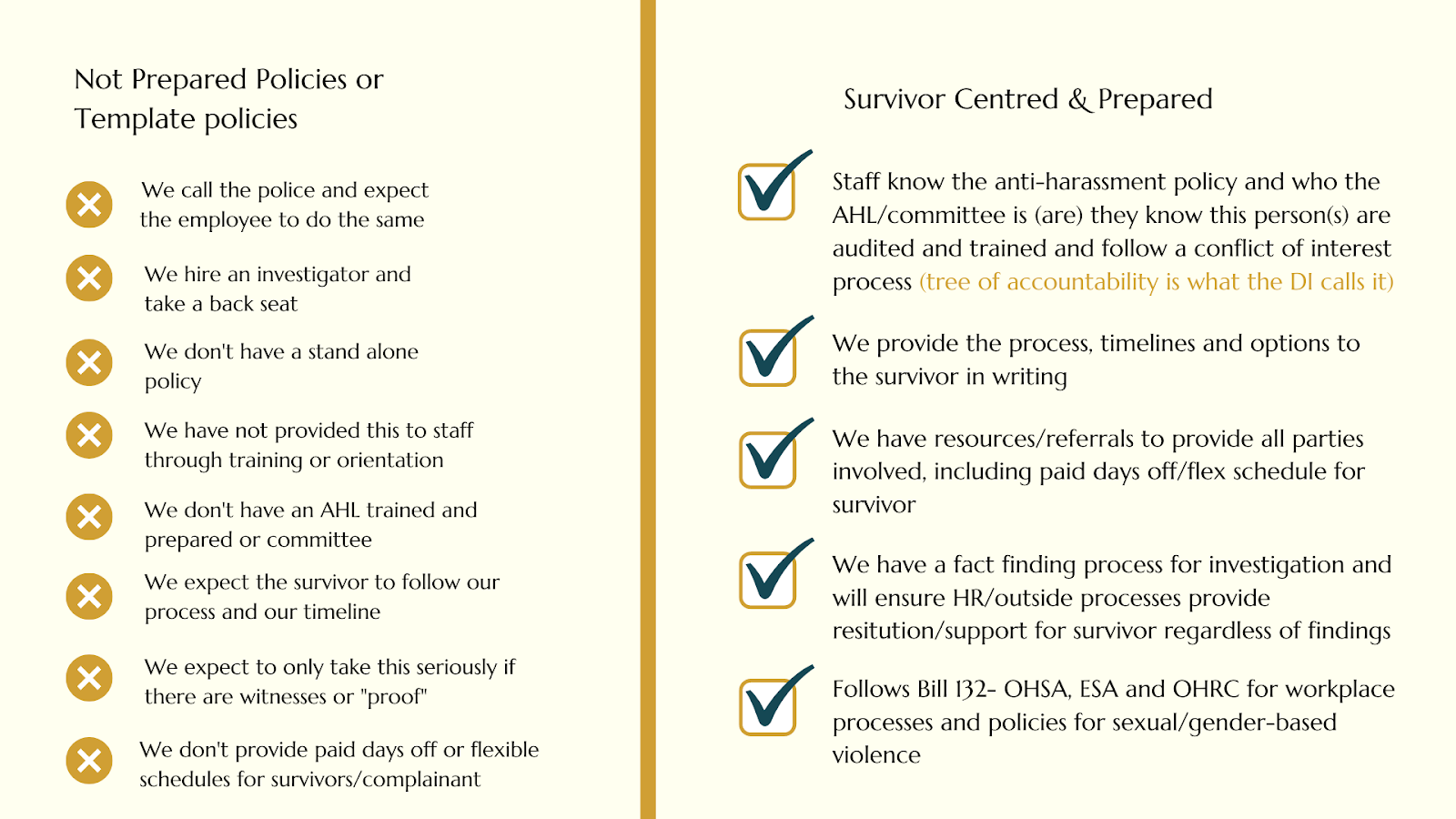

- Explain the difference between a survivor centric response and one that is NOT survivor centric

- Define and apply informed consent practices

- Define sexual harassment and sexual assault

- Explain what a “toxic” work environment means

- Identify and label your bias or privilege and apply this to breaking down power dynamics between yourself and complainants

- Explain why not all survivors respond to react in the same way to trauma or violence

- Understand why survivors do not want to report or disclose often

- Know your workplace policy and understand how to explain the steps, timelines and processes to the survivor or to the person who committed violence/abuse.

- Know the difference between reporting and disclosing

- Provide a survivor centred reporting or disclosing process and have ways to reflect and evaluate your processes

- Identify where you need to delegate or need more learning/training before conducting investigations or taking disclosures

Workplace Sexual Harassment and Gender-Based Violence

The Ontario Human Rights Commission defines sexual harassment in employment as:

“Sexual harassment is a type of discrimination based on sex. When someone is sexually harassed in the workplace, it can undermine their sense of personal dignity. It can prevent them from earning a living, doing their job effectively, or reaching their full potential. Sexual harassment can also poison the environment for everyone else. If left unchecked, sexual harassment in the workplace has the potential to escalate to violent behaviour.

Employers that do not take steps to prevent sexual harassment can face major costs in decreased productivity, low morale, increased absenteeism and health care costs, and potential legal expenses. Under the Ontario Human Rights Code, sexual harassment is “engaging in a course of vexatious comment or conduct that is known or ought to be known to be unwelcome.” In some cases, one incident could be serious enough to be sexual harassment.”

The big question employers and participants in our Now Serving: Safer Bars and Artistic Spaces training ask us is:

Why does this keep happening? Even within great spaces with good teams?

Sexual harassment and gender inequity can happen in all spaces no matter how “great” the team is. If you aren’t sure what we mean, return to the GBV 101 portal and explore the sections on rape culture and myths more before continuing.

Press Progress reports that:

“More than half of all Canadians say women are sexually harassed in the workplace. Seven in ten say their bosses turn a blind eye to sexual harassment targeting women in their workplace”

Did you know?

Even though employers are required by law to take action preventing and responding to sexual harassment, recent polling by Abacus Data suggests it continues to be a widespread problem in most Canadian workplaces. Yet 56% of all Canadians say they’re personally aware of sexual harassment occurring in their workplace – 12% describe it as “quite common.” Troublingly, the survey also finds seven-in-ten Canadians say co-workers who sexually harassed women faced no consequences at all for their actions.

Workplace violence and harassment are not new,

they’re merely so normalized and ignored.

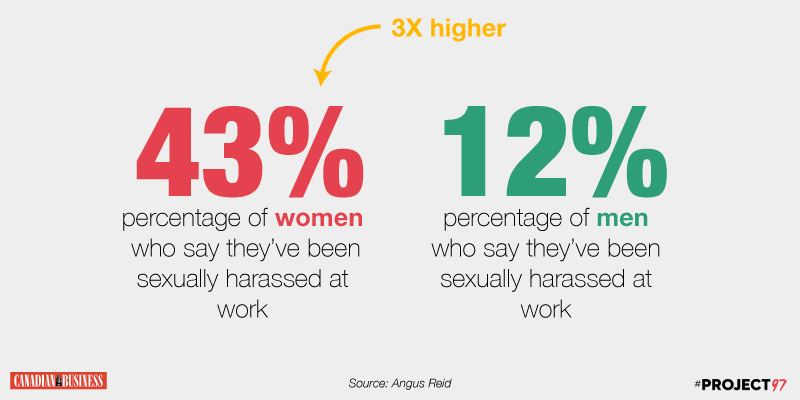

The long term damage and effects of this apathy and inaction leads to grievous outcomes for women, trans people and their communities. In 2018, the Angus Reid Report showed us this stark reality for women and feminized people in the workplace.

The devastation on the individual, their mental health, their families health and the health of your team is too much of a cost. Investing in safety means investing in gender-based violence prevention and response that is survivor-centric and equitable.

Quotes from employees and participants in our training and workshops:

I was told that he was "a nice guy who would never do that." That was my manager’s response when I told him our boss had sexually assaulted me at a staff party and so I never brought it up again and instead I quit.

Safer Bars and Spaces Participant, 2018

I reported it to the police and to my employer, I was fired as soon as the crown dropped the charges against him due to insufficient evidence. It was the reason I relocated to Alberta.

Safer Bars and Spaces Participant, 2019

Without buy in from the top, the staff are just left to either get their own legal support or suck it up, I've witnessed sexual harassment and I've wanted to report it or talk to the person experiencing it, but there's no workplace culture role modeled from the top that made me feel like I wouldnt be causing issues or a whistleblower.

Empowered Bystander Intervention Workshop Participant, 2019

We got your training and it seemed like things changed for a week or so, but as soon as management knew no one would “check in” on them everything went back to the toxic culture it was before.

Now Serving: GBV prevention at work training participant, 2020

They hired an investigator that was clearly hired to protect the company image and liability. It was a horrible process and it was never spoken about after.

Safer Bars and Spaces Participant, 2019

Here is what 100 women and non-binary professionals and employees in the Hospitality and Live Music Industry reported back to the Dandelion Initiative in 2019 when we asked:

What would you need to feel safer at work?

A culture that discourages harassment, violence, bullying, sexism, racism, etc and management that is easy to talk to if something arises.

Policies around sexual violence that are shared with all staff no matter their level of 'importance,' as well as the enforcement of those policies.

Transparency of policies, healthy communication, intentional practices, accountability measures that are clear and accessible, workplaces that aren't "politically neutral".

More female management, diverse leadership, and better leadership training to teach management how to address sexual harassment when it arises.

A workplace that values physical, mental, emotional safety. To know I am able to talk to my employers, managers, or other staff members if a guest is making me uncomfortable, or if someone on staff is making me feel unsafe.

Demonstrating values all the time, not just in training / HR environments.

A more structured and professional environment helps feel that there is a clear line between what is and isn’t acceptable behaviour so it’s possible to note when something is crossing a line.

More diverse and queer hires, especially FOH (front of house) staff not just BOH (back of house)

Without education and tools, we can often:

Ignore harm and become complacent to it in the space which increases our collective liability and risks in our workplace.

Create blame instead of proactive solutions or responses.

Feel powerless in risky situations.

React to harm instead of preventing it.

“You have to take WHMIS training to learn why toilet cleaners shouldn’t go in your eyes. You should also have to take sexual-misconduct training.”

To prevent and respond to gender-based violence in the workplace we need a commitment from people in positions of power and leadership to uphold cultures of consent and gender-equity.

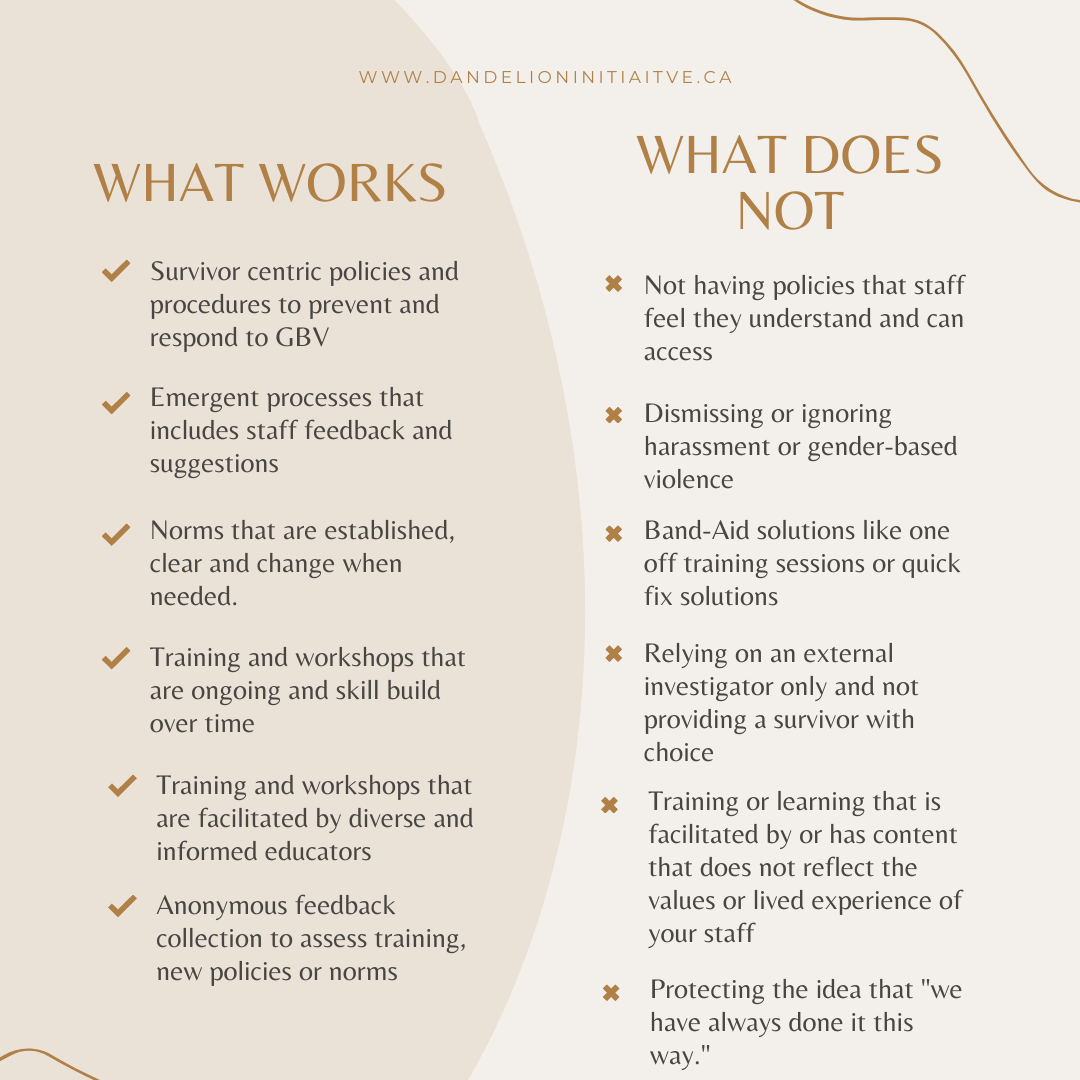

What can work and what doesn’t when it comes to creating workplaces that prevent or respond to gender-based violence?

Creating cultures of consent starts with you and the environment that, as an employer, you create for your teams. Policies are only effective if there is a culture of consent and equity to put those policies into practice.

Shareable from the Dandelion Initiative, 2020.

Did you know?

The New York City Human Rights Commission released a campaign that really highlights why consent is critical in the workplace to maintain safety and mitigate harm.

Opportunity for thinking and reflection

How does this create unsafe spaces/workplaces?

Learn more throughout the portal and stop to visit the Empowered Bystander Intervention page to learn more about privilege, power and consent.

We work and live in a society where inequality is accepted as a part of social norms and behaviour. We learn from an early age who is valued and who benefits from these beliefs when adhered to and perpetuated. When we ignore these behaviours or accept them we are encouraging people to abuse their power and privilege.

Activity #1

Try the Staff and Community Online Safety Scan now before moving onto the next learning section.

Domestic Violence in the workplace

Domestic Violence/Family Violence, also known as Intimate Partner Violence, is dangerous for everyone, not just for the survivors/victims and their children.

Although all people can experience domestic violence, women and children are most commonly subjected. Some women are more vulnerable to family violence or face increased barriers to accessing domestic violence services or support.

Domestic Violence is not just a family or private issue, it is a workplace occupational hazard that you can prevent and respond to.

If you are an employer, in Ontario you will need to ensure you have a domestic violence policy and procedures either stand-alone or as part of your workplace anti-sexual harassment and gender-based violence policy.

The following stats and research are referenced from Guidelines for developing workplace domestic violence policy.

54% of domestic violence victims miss three or more days of work a month.

25% of employees have experienced domestic violence.

22% of workers report that they have worked with someone who has been a victim of domestic violence. Domestic violence often follows victims to work.

Most women (70%) suffering from domestic violence are victimized at work.

The most common things that abusers do are:

calling over and over to harass the victim

showing up at the workplace to harass the victim

watching the victim from across the street

contacting their co-workers or friends while they are at work to determine their location

Domestic Violence and Your Duty to Report

It is not the employer’s responsibility to report domestic/sexual violence to the police outside of a workplace investigation unless this person is held to a standard of practice with a duty to report, which your professional college or advisory would notify you of.

Did you know?

If an employer calls the police or initiates a formal investigation without the survivor/victim’s knowledge or consent or if the employer coerces or pressures the employee, she or they may experience increased violence at home and/or separation from their children? It often does not help the survivor. It also increases the chance of severe harm to the survivor/victim from not only their abuser but from various systems as well.

Did you know?

Everyone in Ontario has a duty to report child abuse Reporting abuse and neglect.

What is the law in Ontario, really?

The Occupational Health and Safety Act states that it is an employer’s duty to take all reasonable precautions to protect a worker from domestic violence at work (s 32.0.4).

This means if you believe a worker is experiencing domestic violence, intimate partner violence, and/or family violence, it is your obligation to check in with that employee and offer support and resources.

You cannot formally report this or call the police without the victim’s consent.

Domestic violence is a collective issue, not a private issue and with many people working from home it is now more than ever a workplace issue.

Read more through our shareables below and keep going with this good learning!

Are you interested in learning what a domestic violence prevention and response policy could look and sound like? Read our Learning Brief on Domestic Violence in the workplace.

Questions and Offerings

So, how can I tell if someone at work is experiencing violence and what can I do?

The best way to check in or bring offerings to the table is slowly and without pressure. You can be really honest and up front or you can use other methods. Regardless of what you do to offer support, remember it is not about you or your feelings. The survivor/victim may reject your help and please don’t take that personally, remember your privilege in the situation and just continue to treat the survivor with respect and fairness.

Some ways to check in or offer support:

Offering companionship “Hey Linda, If you ever want to just go for a walk during our lunch break I would really like the company.”

Offering your phone number “Hey Lou, here is my cell number, if you ever want to chat after work I’m a great listener and friend”

Offer resources and actions like this guy below:

- If you witness clear signs of abuse or stalking from the abuser, sometimes simple and clear language is best. See it, Name it, be trauma-informed about it.

“Sarah, I am worried about you and your safety and I have resources to help you. Do you know what your options are? How can I help you.”

“Dani, I’ve noticed you have been late for work a lot lately, is something wrong? Are you ok?”

“I overheard your partner screaming at you again on the phone/in the hall/outside, I am worried about you and I am here to talk in confidence. You are not alone or to blame.”

Express concern and open the door, you will have resources and support to guide you through in your workplace, review your policy and call a shelter or women’s organization to help you if you need additional resources.

What are signs of abuse in the workplace?

Adapted from: Warning signs, Canadian Labour Congress, Canada.

Some warning signs that someone may be experiencing domestic violence may include:

Physical injuries such as broken bones, a black eye or loss of hearing, which people who are experiencing abuse may attribute as “accidents” or “from being clumsy”

Inappropriate clothing for the season (such as long sleeves or turtlenecks in the summer or wearing sunglasses indoors)

Uncharacteristically late or absent from work, wanting to work extra hours to avoid going home

Change in job performance: errors, slowness, lateness, absenteeism, lack of concentration

Sudden signs of anxiety and fear

Making special work requests (such as to leave work early)

Generally acting isolated and quiet

Emotional distress including sadness, depression, or suicidal thoughts

Minimizing or denying harassment or injuries

Excessive phone calls, emails or text messages. Reluctance to respond to phone messages. Others at work may overhear or witness insulting messages intended for the victim

Sensitivity if people ask about home life or trouble at home

Disruptive visits in the workplace by past or current partner

Fear of job loss

The sudden appearance of gifts (such as flowers) after an apparent dispute between the couple

These warning signs are intended to help direct your intuition and ask questions. Never jump to conclusions. Even if you think someone may be abused according to these warning signs, it does not mean that they are in an abusive relationship. Allow this list of warning signs to spark dialogue with a member. Remember that the most dangerous time for women separating from an abusive partner is just before she leaves, when she leaves and just after she leaves! Even though separating can make you safer in the long run, you need to be very careful when you decide to separate and as you go through the separation process. To protect yourself, get help. Call the local women’s shelter or Assaulted Women’s Helpline at 1.866.863.0511 or TTY 1.866.863.7868

What is Sexual Assault & Harassment?

Legal Definitions

Sexual violence is rooted in gender hierarchies, dominance, and unequal power arrangements based on misogyny and racism. It is not an act of sexual desire; it is a crime of disempowerment and violence.

-

Canada has a broad definition of sexual assault.

-It includes all unwanted sexual activity, such as unwanted sexual grabbing, kissing, and fondling, as well as rape.

-Sexual activity is only legal when both parties’ consent.

-Consent is defined in Canada’s Criminal Code in s. 273.1(1), as the voluntary agreement to engage in the sexual activity in question.

-The law focuses on what the person was actually thinking and feeling at the time of the sexual activity.

-Sexual touching is only lawful if the person affirmatively communicated their consent, whether through words or conduct.

-Silence or passivity does not equal consent.

The Canadian Criminal Code also says there is no consent when:

-Someone says or does something that shows they are not consenting to an activity.

-Someone says or does something to show they are not agreeing to continue an activity that has already started.

-Someone is incapable of consenting to the activity, because, for example, they are unconscious.

-The consent is a result of someone abusing a position of trust, power or authority.

What can sexual assault look like?

-Touching that was not asked about first (assumed consent) touching that is consistent and ignores all verbal and nonverbal cues to stop.

-Forcing sexual acts, this also includes coercion (cannot say no) and bargaining (debating a no or lack of yes).

-Drugging and dosing someone to alter their state of mind. This also means offering someone more drinks when they have clearly had enough.

-Retaliation to the word “no” with physical force.

-Using a position of power to influence or pressure.

-

A type of discrimination based on sex. When someone is sexually harassed in the workplace, it can undermine their sense of personal dignity. It can prevent them from earning a living, doing their job effectively, or reaching their full potential.

While sexual assault refers to unwanted sexual activity, including touching and attacks, sexual harassment can encompass discriminatory comments, behaviour, as well as touching.

Sexual harassment may take the form of jokes, threats, comments about sex, or discriminatory remarks about someone’s gender.

Gender-based violence falls under sexual harassment if you are degrading someone’s body, gender, identity, or sexual orientation.

Note for Employers: Sexual harassment can also poison the environment for everyone else. If left unchecked, sexual harassment in the workplace has the potential to escalate to violent behaviour.

Examples in Law

A breakdown and clear examples from the Ontario Human Right Commission Policy on Preventing Sexual and Gender-Based Harassment

-

In the Ontario Human Rights Code (the Code), sexual harassment is “engaging in a course of vexatious comment or conduct that is known or ought to be known to be unwelcome.” In some cases, one incident could be serious enough to be sexual harassment.

The reference to comment or conduct "that is known or ought reasonably to be known to be unwelcome" means that there are two parts to the test for harassment. First, we have to consider if the person carrying out the harassment knew how their behaviour would be received. Second, we must consider how someone else would generally feel about the behaviour – this can help us think from the perspective of a person who is being harassed.

-

Section 10 of the Code defines harassment as “engaging in a course of vexatious comment or conduct that is known or ought to be known to be unwelcome.” Using this definition, more than one event must take place for there to be a violation of the Code. However, depending on the circumstances, one incident could be significant or substantial enough to be sexual harassment.

Example: A tribunal found that an incident where a male employee “flicked the nipple” of a female employee was enough to prove that sexual harassment had taken place.

The reference to comment or conduct "that is known or ought reasonably to be known to be unwelcome" establishes a subjective and objective test for harassment. The subjective part is the harasser’s own knowledge of how his or her behaviour is being received. The objective component considers, from the point of view of a “reasonable” third party, how such behaviour would generally be received. Determining the point of view of a “reasonable” third party must take into account the perspective of the person who is harassed. In other words, the Human Rights Tribunal of Ontario (the HRTO) can conclude on the basis of the evidence before it that an individual knew, or should have known, that his or her actions were unwelcome.

It should be understood that some types of comments or behaviour are unwelcome based on the response of the person subjected to the behaviour, even when the person does not explicitly object. An example could be a person withdrawing, or walking away in disgust after a co-worker has asked sexual questions.

Human rights case law has interpreted and expanded on the definition in section 10 of the Code. In one of the earliest sexual harassment cases in Canada, a tribunal found that in employment, discriminatory conduct may exist on a continuum from overt sexual behaviour, such as unsolicited and unwanted physical contact and persistent propositions, to more subtle conduct, such as gender-based insults and taunting, which may reasonably be perceived to create a negative psychological and emotional work environment.

Human rights law clearly recognizes that sexual harassment is often not about sexual desire or interest at all. In fact, it often involves hostility, rejection, and/or bullying of a sexual nature. For more information, see the section entitled “Gender-based harassment.”

-

A person may be especially vulnerable to sexual harassment when they are identified by more than one Code ground. For example, a young lone mother receiving social assistance who has had trouble finding suitable housing for herself and her child may find it very challenging to move when her landlord continues to proposition her sexually after she has said no. This woman’s sex, age, family status and receipt of social assistance all make her vulnerable to sexual harassment. If she is a racialized person or has a disability, her experience of the harassment may change or be compounded.

Where multiple grounds intersect to produce a unique experience of discrimination or harassment, we must acknowledge this to fully address the impact on the person who experienced it. Where the evidence shows that harassment occurred based on multiple grounds, decision-makers should consider the intersection when thinking about liability and the remedy available to the claimant.

Tribunals and courts have been increasingly using an intersectional approach in the human rights cases they hear. For example, in one case alleging sexual harassment in employment, the tribunal recognized the claimant’s identity as an Aboriginal lone mother as helpful in understanding the choices available to her when she was trying to keep her job and cope with the respondent’s behaviour. The tribunal stated:

[T]he complainant’s gender, her status as a single mother and her aboriginal ancestry combined to render her particularly vulnerable to the conduct of the respondent.

In another case dealing with the sexual harassment of a woman in the workplace, the tribunal stated in its decision:

As for her vulnerability, it was undoubtedly increased by the fact that as a lesbian, she was a member of a marginalized group.

The harassment provisions of the Code (subsections 2(2), 5(2), 7(1) and (2)) specifically prohibit harassment based on sexual orientation.

Research has shown that unmarried women may be more vulnerable to sexual harassment in the labour market than married women, due to a perception that they are less powerful. Young women, as well as women with disabilities, may be similarly singled out as targets for sexual harassment due to a perception that they are more vulnerable and unable to protect themselves.

Racial stereotypes about the sexuality of women have played a part in a number of sexual harassment claims. Women may be targeted because of beliefs based on racialized characteristics (for example, they are more sexually available, more likely to be submissive to male authority, more vulnerable, etc.).

Example: A woman of mixed Métis and Black ancestry experienced a serious course of sexual comments by her employer, who repeatedly referred to his preference for Black women and the physical characteristics of Black and African women. She was also subjected to physical touching and pornography. The tribunal found that her employer sexually and racially harassed her because she is a young Black woman that he, as her employer, could assert economic power and control over. He repeatedly diminished her because of his racist assumptions about the sexuality of Black women. The tribunal awarded separate monetary damages for the racial and sexual harassment. The tribunal also found that the intersectionality of the harassment and discrimination made her mental anguish worse.

In a similar case, an employer’s sexual harassment of a female employee included derogatory references to her race and comments about what he believed to be the sexual habits and preferences of Black women. Sexuality is sometimes intertwined with racism. People may hold stereotypical and racist views about someone’s sexuality based on their ethno-racial identity, and these views may be behind some forms of sexual harassment.

A person may also experience sexual harassment or a poisoned environment because they have a relationship with a racialized person. For example, a woman may be subjected to inappropriate sexual comments because she is dating a racialized man.

Women who come to Canada from other countries to work as domestic caregivers (or “live-in caregivers”) may be especially vulnerable to sexual harassment. They are typically required to live in the homes of their employers, they are isolated, and they need their employer’s cooperation to get citizenship status. For more detailed information, see the section entitled “Sexual harassment in employment.”

What is an Anti-harassment Lead (AHL) or in Ontario sometimes known as an Anti-harassment officer (AHO)?

An anti-harassment lead or officer, will be designated and paid through their workplace or through a volunteering role to act as the first point of contact and support for someone that needs to disclose harassment or violence at work or in a space.

An AHL would typically have the responsibility to:

Be named and listed in the space/company’s anti-harassment and anti-gender-based violence policy as the main point of contact and lead

All staff have access to this lead and the lead has a replacement in case of conflict of interest or other reasons the lead could not provide support and receive disclosures

AHL has been trained in human resources, trauma-informed care, human services or Law.

AHL is informed and knows how to take a disclosure vs a formal report

AHL is survivor-centric in approach

AHL will provide informed consent to all

AHL will role model consent and consent culture

Did you know?

“Having to discuss or disclose sexual violence and harassment can also be traumatic. Even if there may not be physical injuries that can be seen, psychological injuries can be severe, compromising a survivor’s capacity to feel safe in the world and return to work and earn a living.”

As challenging as it can be to receive disclosures of sexual violence, we must remember the impact of ignoring or dismissing disclosures. Ignoring disclosures not only puts the individual in danger but has lasting negative effects on your workplace culture and community because ignoring violence means enabling it. It is also illegal. An employer must ensure an investigation appropriate to the circumstances is conducted.

You do not need to be an expert in sexual violence or counselling to respond to disclosures of sexual violence in informed, survivor-centric ways. The way you respond and the path you take to ensure accountability is critical to a survivor’s health and rights. See our reference list for incredible community facilitators and training options.

Throughout our Now Serving: Safer Spaces Training we have had many profound conversations with HR and staff representatives in AHL roles throughout various sectors. We took our data and feedback from these training sessions and created a list of best practices for developing anti-harassment and GBV prevention and response policies and practices.

Did you know?

Very important for policy developers and employees to know:

There should always be written clarification between an informal disclosure and a formal disclosure. There should always be a clear distinction in writing that shows a survivor/employee the difference between a formal report in the workplace or disclosure to the AHL or lead in hopes of seeking support.

Keep going: Why do you think we recommend this?

Example:

Disclosure: the sharing of information about an incident in hopes of receiving support, more information or other

Report: is the sharing of information with the intention of initiating a process either criminal – reporting to the police or non-criminal, reporting within the workplace through the workplace policy

Most workplaces only have formal reporting options. Why do you think that is?

Important: When a survivor is coming to you to share their story, seek support, disclose or report, you need to make sure that you give them the RIGHT information they need before their disclosure, during or after. You can listen or take down notes: either way, you want to minimize how often or how many times a survivor will have to re-share their experience or the crime with you or someone else.

Tip:

You should never force someone to report something to you. There are special circumstances to all situations, in the case where the person may be a harm to themselves or others a formal report may need to be made to maintain the safety of all those involved. Your workplace policy and workplace safety plan should have these details.

Why do I need to know all of this?

To guide and inform your language, reactions and approaches, many survivors do not disclose because of shaming, disbelief, victim-blaming or re-traumatization. You can mitigate harm by providing survivor-centric responses and processes. If you are in this position, it is a responsibility we hope you take seriously and with dignity.

To ensure you are providing clear directions and options for control to the person disclosing, many AHL’s operate based on their internal policy however, never share those policies with the survivors/employees. Make sure you give informed consent and let the survivor know all their options before offering to support them in their decision-making.

To provide choices that are fair and equitable and meet OHSA standards, the CODE and the Law.

To ensure that you conduct your documentation and “investigation” in safer ways. Many AHL’s and HR approach investigating reports of sexual harassment and violence as “investigating like a cop or judge.” This is NOT survivor-centric and also not best practice.

You are not a police officer or a judge, you are investigating by:

Collecting statements in survivor-centric ways

Collecting documents

Organizing timelines and events or event description

Notifying and organizing the communication between the company and the complainant and or defendant

Providing UNBIASED feedback to the decision-making committee or person

To empower the survivor, your space, yourself and your workplace consent culture.

Challenge for all people responsible for workplace disclosures, reports or investigations

All AHLs should be able to answer these questions and provide survivors with support if they have accepted this role and paid for this role. If you need to explore the website more please do so and reach out for training or support from organizations and professionals that provide these services.

- Who are the victims of sexual and gender-based violence?

- What is the difference between a disclosure and a report- informal or formal?

- What does sexual harassment or gender-based violence look or sound like?

- What are some resources for people who have experienced sexual violence?

- Why would it be more dangerous for a trans or non-binary person to disclose sexual violence in the workplace?

- Why would it be more dangerous for marginalized or racialized women to disclose sexual violence in the workplace?

- Why don’t people disclosure sexual violence or harassment sooner?

- Why don’t they just go to the police?

- How do I know they are telling the truth?

- Can I get in trouble if I ignore the disclosure?

- Can I get in trouble if I ignore a “toxic” work environment?

- What if I am wrong and the person is innocent?

- What is Bill 132?

- What is my workplace policy and where is it located?

- What does an investigation look like?

- What does accountability look like in the workplace?

- What is my role as an AHL?

- What are community or survivor centred alternatives?

- What is survivor centric? Can I explain one pillar for survivor centric practice?

- What is your greatest survivor centric skill to bring to the table as the AHL?

Believe survivors. Change the culture.

Activity #2 & #3

Try the Receiving Disclosures Activity and Anti-Harassment Lead (AHL) Scenario and Reflection Activity now before moving onto the next learning section.

Workplace Sexual Harassment Processes

This section applies to all paid and unpaid workers in Ontario.

Example: I am 22, I work full time, no benefits, for a restaurant, my boss grabbed my chest/breasts, I'm scared to report it and get fired- what can I do?

Check out your workplace policy (if you have access to it). The policy should have at least two people to reach out to in order to report. If you feel okay reporting to that other person, that is your first step.

When you report, you can request confidentiality. That being said, it will only be respected to a point since they have a duty to ensure a safe work environment which could be directly threatened by sexual harassment.

In the case that you are not kept confidential, you can request that during the investigation you and your boss be kept separate. They are not legally required to do this but many places will.

It is not legal to fire someone for reporting sexual harassment.

The Ontario Human Rights Code prohibits reprisal or “payback” where a person raises issues or complains of sexual harassment. Reprisal includes such things as being hostile to someone, excessive scrutiny (for example, at work), excluding someone socially or other negative behaviour because someone has rejected a sexual advance or other proposition (such as a request for a date).

If this isn’t respected and you are fired or otherwise penalized for your report, you can: contact 1) Ontario’s Ministry of Labour and 2) Ontario Human Rights Tribunal

During the reporting and investigation process, you can take a sexual violence leave. You can also take sexual violence leave(s) after the process for healing commitments like counselling.

Work refusal

If reporting is not possible, does not go well, is not taken seriously, or makes working at your job unsafe or otherwise inhospitable, you have other reporting options. Main options are:

human rights

the criminal code

What counts as workplace sexual harassment?

Making a sexual advance at someone when the person making the advance has the power to grant or deny something or otherwise incentivize the response they want. This can look like:

demanding hugs

invading personal space

making unnecessary physical contact, including unwanted touching, etc.

using language that puts someone down and/or comments toward women (or men, in some cases), sex-specific derogatory names

leering or inappropriate staring

making gender-related comments about someone’s physical characteristics or mannerisms

making comments or treating someone badly because they don’t conform with sex-role stereotypes

showing or sending pornography, sexual pictures or cartoons, sexually explicit graffiti, or other sexual images (including online)

sexual jokes, including passing around written sexual jokes (for example, by email)

rough and vulgar humour or language related to gender

using sexual or gender-related comments or conduct to bully someone

spreading sexual rumours (including online)

making suggestive or offensive comments or hints about members of a specific gender

making sexual propositions

verbally abusing, threatening or taunting someone based on gender

bragging about sexual prowess

demanding dates or sexual favours

asking questions or talking about sexual activities

making an employee dress in a sexualized or gender-specific way

acting in a paternalistic way that someone thinks undermines their status or position of responsibility

making threats to penalize or otherwise punish a person who refuses to comply with sexual advances (known as reprisal)

Still not sure if what you experienced could be legally considered workplace harassment? Reach out to any of the free legal supports listed at the bottom of this section.

Things to know about workplace harassment:

Accidents don’t count (ex. tripping and falling into someone)

Intention doesn’t erase actions

In the Ontario Human Rights Code, it defines sexual harassment as “engaging in a course of vexatious comment or conduct that is known or ought to be known to be unwelcome.”

That means they consider if 1) the person carrying out the harassment knew how their behaviour would be received and 2) how someone else would generally feel about the behavior

The person does not need to foresee or intend for their actions to cause you harm

When deciding if sexual harassment has happened, human rights tribunals look at the impact the conduct had on the person, and whether this had a discriminatory effect. The intention of the harasser does not matter. A lack of intent is no defense to an allegation of sexual harassment.

Once is enough

Although much workplace harassment continues over days, months, or years, you don’t need to wait until it’s “bad enough” (no such thing!) to report workplace harassment. Once is already too much.

One “yes” isn’t a “yes” forever

Whether or not you consented to certain behaviours or actions before does not mean you cannot change your mind (ex. If you were once in a relationship with another worker)

You don’t have to object when it happens

There are many reasons why you may not have said anything when the harassment took place. The violation is still real and still illegal whether you objected when it happened or not.

A workplace isn’t always a physical space

Events that take place outside of the workplace like industry events and supplier meetings, office parties, company trips, etc, still count as a part of your “workplace”

When workplace harassment becomes a criminal offense

You can take your case to criminal court if the harassment involves attempted or actual physical assault, including sexual assault, or threats of an assault. Stalking is also a crime called “criminal harassment.”

Who can cause the harm?

Another worker (no matter if their position is above, below, or equivalent to yours)

Any other person who is harmful in the workspace. That means…

A partner, friend, or family member who visited you at work (anyone who has a personal relationship with a worker in the space)

A client

A customer

Process(es) of reporting sexual harassment

General Process

In-work complaint > unsatisfied > Human Rights Legal Support Centre OR Human Rights Tribunal of Ontario (for human rights violations) OR criminal court

In-Workplace Process

Complaint is given to employer or other designated party (employer must list another person besides them in policy) > complaint or incident is investigated by employer and/or employers supports > conclusion > restitution (if complaint is substantiated)

Basic complaint and investigation process:

Interviews with the complainant, respondent, and relevant witnesses.

This interviewing process is not guaranteed to be done separately/individually

Still, most workplaces will keep interviews separate at the survivors request

Review of all relevant evidence.

A written report containing the allegations, response, evidence, findings of fact and a conclusion about whether or not workplace harassment was found.

The results of the investigation and any corrective action must be communicated in writing to the alleged victim and the alleged harasser.

All processes have different steps and different requirements. For example, you can take your case to criminal court if the harassment involves stalking, attempted or actual physical assault, including sexual assault, or threats of an assault.

Human Rights Legal Support Centre Process and Requirements

Human Rights Tribunal of Ontario Process and Requirements

Criminal Court Process and Requirements

Things to know about the process of reporting

Confidentiality to a point

When you tell your employer or other designated point person about sexual harassment in the workplace they can only keep you anonymous to a point since they have a duty to ensure a safe work enviroment which could be directly threatened by the sexual harrassment

If you want to file a formal complaint, you would have to identify yourself as the complainant

Who reports

You, for yourself

It is most common that the person on the receiving end of the harassment reports the harassment

Bystanders

You are still able to file a report in situations where you see something that makes you uncomfortable (and you read as harrassment) but you were neither the person on the acting or receiving end

Even when you are not directly involved in the exchange you can still report the situation if you perceive that the interactions are poisoning the work environment

Evidence or proof

The civil standard of proof is proof on a balance of probabilities. The criminal standard is proof beyond a reasonable doubt. Unless you’re going through a criminal process, any other process should follow the civil standard of proof meaning that you balance both sides and see which side has the stronger proof. Unlike criminal court, proof doesn’t have to be “beyond a reasonable doubt”. Instead, it just has to be more probable than 50%

In cases where there were no witnesses, the credibility of both parties is examined and whoever is seen as more credible wins

In this case, credibility is decided by:

If testimony is clear, forthright, detailed, internally consistent

How questions are answered, if those answers are evasive or not

Consistency of testimony

If explanations are considered implausible or nonsensical

If the witness lies or changes their story on cross-examination

What helps credibility:

Taking notes that record what happened, when it happened, where it happened, what was said or done, who said or did it, and who, if anyone, saw it

Having more than one person who has experienced similar behaviour from the same individual. This “similar fact evidence” can be introduced as evidence to substantiate the allegations

Having other evidence

Where to go for help

In your workplace

Your employer or other designated party (employer must list another person to bring concerns to besides them in your workplace policy)

If available, your workplace contact for confidential support (ex. Human resources or employee assistance program)

Your union

If you are unionized, try contacting you union for support around harassment.

Office of the Worker Adviser

If you are not a member or a union and you think your employer has threatened or punished you for exercising your rights under the OHSA, contact the Office of the Worker Adviser for advice.

Ontario’s Ministry of Labour

If your employer does not have a workplace harassment policy or program and/or did not provide that information, you can contact the Ministry of Labour

You can also contact the Ministry of Labour about a workplace harassment complaint if your employer fails to conduct an investigation that is appropriate in the circumstances.

They won’t look into your individual issue but they may come in and investigate to decide if your employer is meeting their obligations under the Occupational Health and Safety Act (OHSA).

If it falls under the OHSA they will conduct a field visit. You will be kept anonymous if requested. The inspector will complete a field report which may include 1) findings related to your complaint, and 2) written orders against those (workers or employers) who are not following the law.

Ontario’s Ministry of Labour cannot:

Resolve or mediate specific allegations of harassment in the workplace

Investigate allegations to determine was or wan’t workplace harassment

Order individual remedies such as monetary compensation to individuals who experienced harassment in the workplace

Ontario Labour Relations Board

If you feel that you’ve been reprised (retaliated against for your complaint) you can file a complaint with the Ontario Labour Relations Board (OLRB).

The Victim Quick Response Program + (VQRP+)

Process

Human Rights

To talk about your rights under Ontario’s Human Rights Code (which prohibits discrimination and harassment based on a protected ground such as race, colour, creed, place of origin, sex, ethnic origin, citizenship, sexual orientation, gender expression, gender identity, record of offences, age, disability, religion, ancestry, marital status and family status), contact the Human Rights Legal Support Centre

To file a human rights application, contact the Human Rights Tribunal of Ontario (HRTO)

An application/complaint should be filed within a year of the last instance of sexual harassment. Sometimes the HRTO is flexible (they have discretion) but it is best done within the year of the incident.

Law Society Referral Service

You can request the name of a lawyer or paralegal who will provide up to 30 minutes of free consultation to explore your options. A crisis line is also available.

Police

If you have been suffered a criminal offence such as assault, sexual assault, stalking, or are in immediate danger, please call 911.

Criminal Code

Sexual harassment becomes a criminal offence when it involves attempted or actual physical assault including sexual assault or threats of an assault. Stalking is also a crime.

For many of these options, you don’t have to choose one over the other.

You can file complaints overlapping in the big three: 1) in-workplace, 2) human rights, and 3) the criminal code, if you meet the requirements.

Possible restitution

Discipline and terminations (employers are required to abide by the terms of applicable collective agreements)

Financial compensation

Systemic remedies (meaning training and education for the harasser and/or the organization, review of policies and procedures of organization, etc)

Perpetrator is criminally charged

Other

Free legal supports

Please remember that the outcome of any of these processes does not change the truth of your experience. We believe you.

Sources for the Workplace Sexual Harassment Processes section

http://www.ohrc.on.ca/en/policy-preventing-sexual-and-gender-based-harassment-0

http://www.ohrc.on.ca/en/book/export/html/10985

https://www.leaf.ca/the-law-of-consent-in-sexual-assault/

https://www.labour.gov.on.ca/english/hs/topics/workplaceviolence.php

Well done, you’ve reached the end of the Workplace GBV section of the learning portal!

Remember to take breaks and practice self-care in between sections. This can be difficult content. If you need extra support or are feeling triggered, access the resources on the trigger warning page.